ENTITRE

a tribute to physical matter in the digital age.

The ultimate sunbeam - the Luxor tekhenu on Place de la Concorde

How did a 3,300 year old Egyptian masterpiece end up on one of the largest public squares in Paris?

The story of the Luxor obelisk on Place de la Concorde in Paris is one of the many occurrences that chronicle Egypt’s coveted cultural heritage and echoes its past defilement by Western conquests and occupations.

The Luxor Obelisk, prepped and primed for the 2024 Paris Olympics.

The Romans, the first obelisk smugglers

The Romans were the first to deprive Egypt of its ancient obelisks and present them as trophies of war. In 31 BC following emperor Augustus’ defeat over Cleopatra, two obelisks were seized from the Heliopolis Temple and brought back to Rome from Alexandria.

The first obelisk was erected on the Campus Martius and later relocated on the Piazza Montecitorio where it received its title. The second was erected on the Circus Maximus and was also relocated and later raised in the Piazza del Popolo where it stands to this day. Currently, Rome still holds the most obelisks outside Egypt with 18 in total and 48 during the peak of the Roman Empire.

The Fountain of the River, Place de la Concorde, Paris, 2024

The Luxor obelisk, Place de la Concorde, Paris, 2024

When tekhenus became obelisks

The displacement and reappropriation of Egypt’s legacy by imperialist powers is a pattern that can be observed throughout Egypt’s history. Before the Romans called obelisks “obeliscus”, these monumental sunbeams were referred to as “tekhenus” by ancient Egyptians.

“Tekhenu” meant “to shine” or “to pierce the sky”. They were dedicated to the sun-god Ra and were a symbolic representation of the sun’s rays. The word obelisk appeared centuries later and derives from the Greek word “obeliskos” which meant “pointed pillar” and ostensibly holds much less significance than its original name.

Temple of Luxor Facade, watercolour, François-Charles Cécile, 1800

Britain and France’s colonial ventures in Egypt

Subsequent to the Romans, the French and the British were the next empires to exploit Egypt’s extensive ressources and cultural heritage. During the Ottoman Empire, Egypt became a battling ground for the French and the British who spent years fighting to expand their influence and power in the Mediterranean.

Napoleon tried, but failed

It is reported that Josephine de Beauharnais’ parting words to Napoleon Bonaparte before he left for his conquest of Egyptian land were “ Goodbye! If you get to Thebès, do send me a little obelisk”. Considered by colonial empires as booty to be plundered, obelisks continued to be used as symbols of power and hegemony of one empire over the other. However, Napoleon was defeated by the British, and Josephine never gifted an obelisk.

So how did the Luxor obelisk make it to Paris?

A race between two powers for the “civilised acquisition” of an obelisk

Before Egypt fell under British protectorate, it was under the Ottoman Empire and ruled by the Albanian sultan Mohammed Ali Pasha. During his reign, Pasha gifted an obelisk to the British Empire to commemorate their winnings against the French in 1801. While the British welcomed the gift, they refused to fund its perilous journey. The obelisk was moved from Cairo to Alexandria and awaited transport to London for 57 years when eventually, a generous philanthropist by the name of Sir William James Erasmus Wilson decide to fund and oversee its transfer to London.

This delay enabled France to secure an obelisk of its own in the meantime. Indeed, initially not one but two carved obelisks placed at the entrance of the Luxor Temple during Ramses II’s reign were gifted to King Charles X by the Viceroy of Egypt Muhammad Ali in 1829, as a diplomatic gesture. This came after Jean-François Champollion, a passionate French historian and linguist found the key to the decipherment of the Rosetta Stone’s hieroglyphs in 1822. But unlike the English, the French were determined to obtain an obelisk of their own and were not discouraged by the cost and difficulty of transporting it to Paris.

Champollion himself was entrusted with choosing which obelisk was to leave Luxor first. After much research, the right obelisk upon entering the Temple was chosen as Champollion considered it was more congruous to a French audience. Champollion believe the other obelisk to be damaged at the base and it was therefore left behind.

The Luxor Temple entrance after the removal of the obelisk chosen by Champollion.

engraving by David Roberts, 1838

A foreign jewel placed at the center of Paris’ revolution square

A close up of the base of the Luxor obelisk, on display at the Louvre-Lens museum

When the obelisk arrived in Paris, it took another three years to be erected. On the obelisks’ base statues of baboons standing on their hind legs with their arms raised and their reproductive organs exposed were considered too libertine for the prude Parisian audience of the time and were taken down which further delayed the obelisk’s erection. Today the base can be found at the Louvre-Lens Museum.

watercolor painting by Cayrac depicting the erection of the Luxor Obelisk on the Place de la Concorde in 1836

Then came the time to decide where to place the monumental granite sunbeam. The place de la Concorde was deemed the perfect location, a symbol of France’s tumultuous past it would reconcile the French following the revolution.

With the help of the Apollinaire Lebas, the young engineer who oversaw the transportation and installation the obelisk from Luxor to Paris, it was finally raised in 1836 in front of 200,000 curious spectators.

Considered too risky and too costly, the second obelisk never made it to France, and was officially handed back to Egypt by president Mitterand in 1981.

At the base of the Luxor obelisk diagrams show how the obelisk was lowered in Egypt

and raised in Paris.

The Republican Guard, Place de la Concorde, Paris 2024

Beirut, The Eras of Design - a pioneering exhibition on design in Lebanon at MUDAC

Richard Yasmine’s AFTER AGO collection of tables and vessels

When curator Marc Costanini stumbled upon the works of designers Karen Chekerjian in Paris and Marc Dibeh during a group exhibition in 2016 - his curiosity was sparked. The need to put together an exhibition centred on design in the Middle East and specifically in Lebanon - a pioneer of its kind, became apparent. Before it, no study had been conducted on the history of design from the country’s independence to the present day.

MUDAC - Lausanne’s Museum of Contemporary Design and Applied Arts - is the only institution in Western Switzerland entirely dedicated to design.

Seven years later, the exhibition came to life, Beirut. The eras of Design opened its doors to the public from April 7th to August 6th 2023 at the Museum of Contemporary Design and Applied Arts in Lausanne, Switzerland - with the aim to fill the gap on design in Lebanon; its origins and situation today - a subject left unexplored before then.

The exhibition follows a chronological time frame and is divided into three periods. The starting point being Lebanon’s independence in 1943, followed by the civil war period and the year 2000 when designers began moving back to Lebanon.

Above, a copy of the screen reproduced by maison Tarazi and originally designed by Serge Sassouni in 1959 for Alcazar Hotel in Beirut.

Carlo Massoud’s Arab Dolls.

Thomas Trad’s Eva Paravent.

15 contemporary studios were also invited to take part in the exhibition project and showcase their iconic pieces, telling the story and diversity of design in Lebanon with designers such as Carlo Massoud, Carla Baz and Marc Baroud.

Marc Dibeh, Stone Ops. Marble

Marc Baroud’s marble tables

The exhibition designers - Jad Melki and Ghait Abi Ghana from Ghaith & Jad architecture studio were chosen as the exhibition’s set designers. Their fragmented and adaptable installation based on three headed void pedestals convey the idea of fragility at a deeper level mirroring the city of Beirut - its archeological heritage and ever-changing nature.

Marc Baroud, Dot to Dots / Collection 1

Mary-lynn & Carlo Massoud’s BALOO buffet.

These wooden stools are the fruit of a collaboration between Minjara and Maison Tarazi.

The last component of the exhibition is the Minjara projet in Tripoli , installed since 2018 in the spacious building designed by Oscar Niemeyer. Its aim - preserve Lebanon’s woodwork heritage and to foster dialogue between traditional craftspeople and contemporary designers in a spirit of innovation.

Alongside the exhibition, a book “Beirut, the eras of design” was published. It was co-edited by Kath Books x Music Lausanne and is the first of its kind on design in Lebanon. It tells the story of the history of design in Beirut, the emergence of contemporary design and the Minjara solidarity and creative initiative.

Discover Penone’s breathtaking piece Luce e ombra, 2011 at the Musée Cantonal des Beaux Arts, opposite the MUDAC during your visit in Lausanne.

ANDRE CADERE unlimited paintings at Fondation CAB

A current show curated by Hervé Bize at Fondation CAB in Brussels shows the work of Cadere until July 15th.

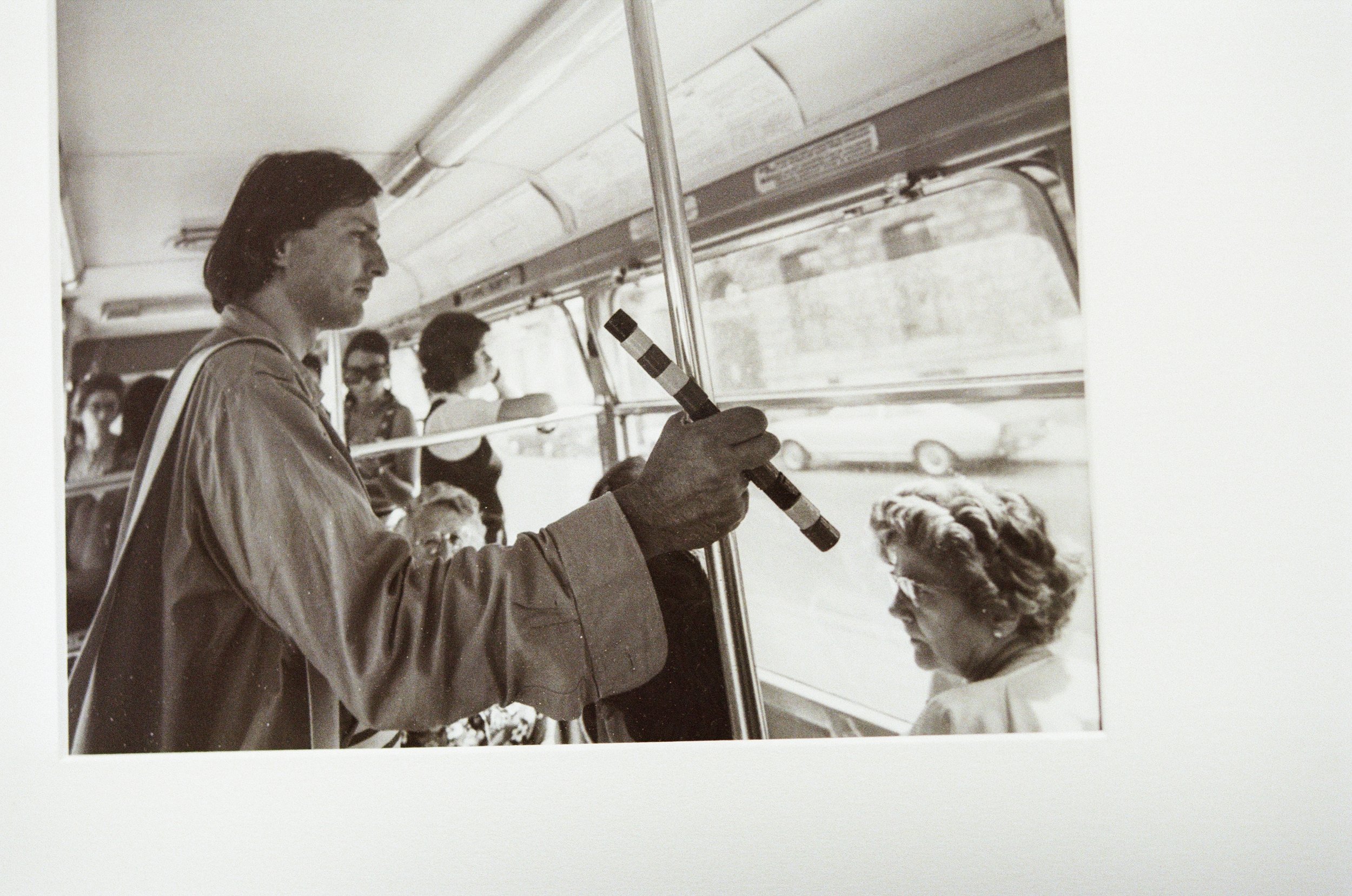

André Cadere wanted to bring the piece of art out of the gallery space.

With merely the body as a véhicule for the pieces, carrying his bars himself.

At LWJ we also believe in the power of physical object and their displacement.

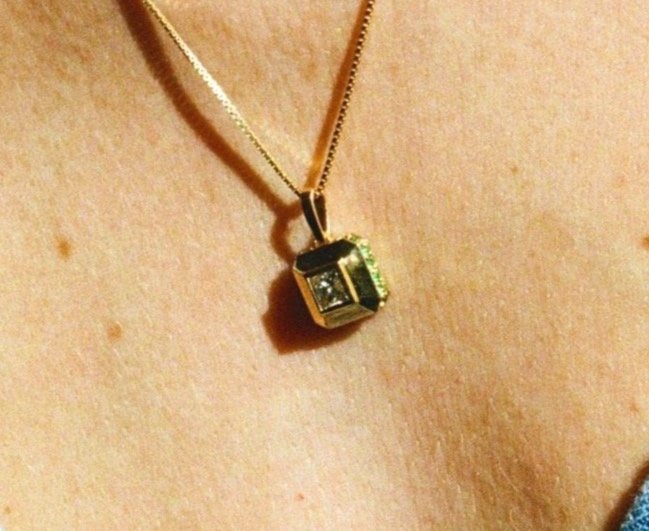

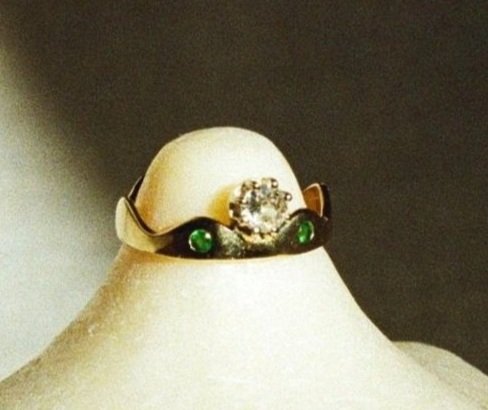

Inspired by Cadere’s work we are thrilled to introduce to you our new lulu w ring VWB BWPR BWGB in size 54 and adjustable.

A beautiful gender-fluid piece that would do a fantastic gift for Daddy’s day.

Mad about malachites

Alicja Kwade, Au cours des Mondes, 2022. An installation place Vendôme curated by Jerome Sans as part of Paris+ by Art Basel’s ‘Sites’ programme.

With it’s psychedelic alternating light green to dark green concentric and banded zonings, there’s a multitude of reasons why the malachite gemstone attracts jewellery lovers and amateurs alike!

This funky green malleable stone is often used in jewellery as it’s easy to work and also relays a beautiful rich and textured look when polished. The malachite derives its colour from the presence of copper in its composition and must be kept away from the heat as it is quite a soft stone (between 3.5-4 on the Mohs scale).

On a lithotherapy level, malachites are believed to resonate with those looking for emotionally balanced and calm relationships. Here are a few of the malachite’s said virtues for those who believe in the power of the stone’s natural vibrations. The malachite will help its wearer to find his place in the world. It favours changes and necessary transformations in the life of its owner so that they align with his heart’s desire as well as meaningful relationships based on love and not on need or dependency. The more regularly the malachite is worn the more it will contribute to a healthy social life. The malachite can also help heal childhood traumas. The malachite will enable its owner to realise if he is in a toxic or unhealthy relationship and act upon it. It favours the imagination and concentration. Holding it whilst meditating will help concentrate in the now.

Outrenoir retreat on the route to Santiago del Compostella

There are many beautiful villages in the Aveyron region on route to Santiago del Compostella but one that is undeniably worth the stop is the ridiculously picturesque village of Conques with it’s unique Romanesque Abbey-church and medieval treasure of goldsmith art.

There are many beautiful villages in the Aveyron region on route to Santiago del Compostella but one that is undeniably worth the stop is the ridiculously picturesque village of Conques with it’s unique Romanesque Abbey-church and medieval treasure of goldsmith art.

Distinctive for its function as a pilgrimage church the Saint Foy abbey church is registered among the World Heritage list. The massive structure made of yellow limestone, pink sandstone and grey-blue schist includes one of the most significant tympanum of the Last Judgment - a masterpiece of Romanesque art, as well as Pierre Soulages’ incredible contemporary glass windows.

Commissioned by the Ministry of Culture in 1986, Pierre Soulages immediately accepted the offer to design the abbey’s stained glass windows. Growing up in Rodez a few miles from Conques, the discovery of St Foy as a child left him in awe and consolidated his desire to pursue an artistic career from that point on.

It took Soulages and his team 7 years of research and testing to create the perfect glass to fill the Abbey-church with light. Unlike the past Gothic figurative and multicoloured stained-glass windows set after World War II, Soulages envisioned a chromatic, natural light and managed to create a translucent glass that was able to block the outside view but not the light from seeping in.

The result is outstanding, depending on the sun’s position and the light each day; the glass windows - divided into oblique lines - can naturally diffuse a chromatic colour scale from dark blue to turquoise or hot orange to yellow or Soulage’ signature luminous white.